The scanning was easy, the posting more so, so now you may enjoy as well!

Rafeeq

| RafeeqMcGiveron.com |

|

|||

|

|

I happened to stop in to The Reading Place over in Charlotte, MI, which is a very fine used bookstore indeed. There I happened to find variations on an early 1960s Signet Green Hills of Earth and a mid-1990s Baen Sixth Column with a John Melo cover, plus an early 1990s SF collection edited by Jerry Pournelle that includes Heinlein’s “The Long Watch.” The scanning was easy, the posting more so, so now you may enjoy as well! Rafeeq

0 Comments

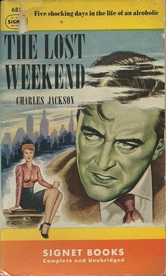

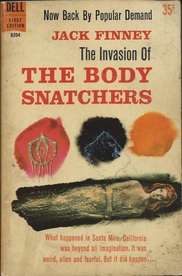

A couple of weeks ago I found a lovely old 1948 Signet edition of Charles Jackson’s 1944 The Lost Weekend at the Reading Place in Charlotte, MI, for $4—a terrific buy. The cover is one of those colorful paintings bootstrapped from the film version, so just as my similar copy of Treasure of the Sierra Madre features Bogart, this one features Ray Milland. After seeing the film so many times, though, it is a surprise to discover that the protagonist actually has a mustache... In any event, the novel is an exquisite 5-star read. Below is the review I did on Goodreads: https://www.goodreads.com/review/show/1147722336 Rafeeq Charles Jackson's 1944 The Lost Weekend is a gripping probe into the mind of an alcoholic--the euphoria and the terror, the self-congratulation and the remorse, the understanding and the turning away. Really, as long as the term probe is used, one might reach next for lancet or scalpel, but of course such would not be fitting. These tools, after all, slice straight and clean, yet Jackson's artful third-person-limited prose and the artfully tipsy stagger of his plotting that hints, reveals, withholds, reveals in bits again is like a corkscrew, or perhaps some piece of fractal geometry that slithers into the corrugations of the brain, and somehow opens the gray matter up for inspection. Many are familiar with the film adaptation starring Ray Milland, which of course is superb for its day, but of course Jackson's original novel is better. Avoiding spoilers, let us just say...well, that the book may not be quite as cheery as the film, perhaps. Many memorable images and scenes from the movie indeed do come straight out of the text: the bottle on the string--but, oh, how long we will wait for this in the book!--the planned trip to the country with brother Wick, the disappointing of bar "hostess" Gloria, the endless sweating stagger to pawnshops closed for Yom Kippur, the woozily confident purse caper in the restaurant, the fall down the stairs and the meeting of the creepy, faintly predatory male nurse Bim, the delirum tremens-induced vision of squeaking, bleeding mouse devoured by carnivorous bat. Whereas Milland's character in his youth actually had been a promising writer, however, with a story published in the Atlantic Monthly, here Don Birnam is a nothing and a nobody. Oh, he had potential, certainly--everyone could see it. His second-grade teacher even wrote a gushing letter to Don's mother, saying that he was the brightest and most promising pupil she had ever had. At age ten the sensitive lad studied his face in the mirror as he cried at the realization that his father truly had abandoned the family and would never come back, and as a teenager he made it a point to write a poem every night, no matter how late he had to stay up. He knows his "Poe and Keats, Byron, Dawson, Chatterton--all the gifted miserable and reckless men who had burned themselves out in tragic brilliance early and with finality"--and this brand of genius of course has an allure to "[t]he romantic boy." Don did not have even a year in college--that little incident with an upperclassman in his fraternity, wherein seemingly natural hero-worship led to a letter rather too warm not to lead to scandal and disgrace with fortune and men's eyes. Nevertheless, he is well traveled and beautifully well read. Switzerland, France, England, Greenwich Village--been there. Shakespeare, Byron, Chekov, Joyce, Fitzgerald--read 'em. But he can imagine being a writer, and writing the great novel of drunkenness and promise and self-deception and revelation, only when half-soused...just as he imagines being a master concert pianist despite not yet having learned to play, or being a great actor despite never having performed, or professing to a class on F. Scott Fitzgerald despite not even having earned a B.A. degree. Many a film makes such alcoholic pretension seem humorous, but just as the Milland version does not, neither has the source novel. The ironies are sad and grim, the situation frustratingly inescapable. Jackson, then, is the great literary revealer that Don Birnam, regardless of his French and his German and his jaunty allusions to works up and down the canon, cannot be. How can a single drink just to start the fun lead to another of seemingly benign effect, then to a larger one, another taken in a gulp, and a few more no longer counted, as reason jumps by flea-hops from topic to topic, grows elliptical, finally sinks into the mire of a blackout? Jackson shows us, in a deeply introspective style that deftly pulls to the surface his central character's submerged motivations, his strengths, and his weaknesses with the same eye for detail that gives us an irresistible seven-page travelogue of the 65-block stagger lower, ever lower, through the socioeconomic strata of New York City. In the end it is Charles Jackson's gritty, forthright, and yet delicately rendered novel itself, not the actions of Don Birnam, that give any hope for the future. 30 December 2014  Some time ago at The Reading Place in Charlotte, Michigan, I picked up a nice 1963 Dell reprint of Jack Finney’s The Body Snatchers—no “invasion of” in the original title, apparently. It was a marvelous read. I cringed whenever the main characters ventured out of each other’s sight. I frowned at their attempted rationalizations of the unbelievable things they had seen. I gaped when, after finally having captured a cop’s service revolver, the protagonist ends up throwing it away because he cannot carry it inconspicuously—Come on, Doc, no jackets in 1955...? Really, though, every sidestep and piece of self-doubt made perfect sense, and it simply set us up all the better for the time when the baddies trot out the fuller explanations. In any event, below is the review I posted at Goodreads: https://www.goodreads.com/review/show/1034719193 Jack Finney's 1955 The Body Snatchers is an exquisitely terrifying story of alien invasion which, despite the basics of its plot having become cultural tropes in the succeeding decades, remains as suspenseful as the day it was released. Point of view, style, and setting here work together to make the unbelievable seem completely possible. First-person narrator Dr. Miles Bennell is the perfect character to deliver this story. The small-town doctor is well-educated, of course, and as a lifelong resident, he has the good general practicioner's eye for detail and tolerant understanding of human behavior, along with an intimate knowledge of the residents, geography, and history of the city of Santa Mira, California, population 3,890. His prose is matter-of-fact, sometimes wry, sometimes mildly self-deprecating, and when he begins by "warn[ing]" us that the tale "is full of loose ends and unanswered questions" and admitting that he "can't say [he] really know[s] what happened, or why, or just how it began, how it ended, or if it has ended," we are hooked. The 1950s small-town setting then allows Finney both a nostalgic backward look and the firm grounding in prosaic reality needed by any good story of extraterrestrial invasion. The direct-dial telephone has been put in only within the previous year, for example, and the sexual tension between the divorced young physician and his divorced high school friend Becky Driscoll, with its mixture of amiable man-of-the-world roguishness and rather touching hesitance, is a subtly rendered portrait of early postwar mores. The familiar streets of the town, the back yards and porches where Miles played as a boy, the countryside where he hunted rabbits with a .22--in the warm sunlit day, all of these belie the seemingly impossible thing, human and yet not, that he and Becky see in the nighttime basement of the grim and frightened Jack and Theodora Belicec. Yet see it they did. Finney here is a master of the night, and much of the action of the novel takes place after the comforting sun has set, in creepy basements lit by a single overhead bulb or by a dim penlight, on deserted roads where anything, anything at all, might wait in the dark beyond the headlights, in locked rooms where to sleep might mean to lose one's very self. Back and forth Finney deftly works us between the utterly shocking evidence seen firsthand at night and the sheepish uncertainty of plausible-seeming explanations in the morning. Clues are parceled out adroitly, and the protagonists' doubts, even as we wish to shake them into immediate understanding, are achingly believable. Yet eventually even these level-headed people must admit to themselves that something awful truly is going on, something inexplicable and threatening, a conspiracy that grows and grows, unseen and unsuspected by anyone but themselves. The era of The Body Snatchers was, of course, ripe for such beautiful literary paranoia. Once the war had been won and the world apparently made safe for American ideals again, why, new threats suddenly lurked everywhere. The Berlin Blockade of 1948 brought American and Soviet armed forces to a precarious standoff in Occupied Europe, while the hugely populous former ally of China fell to Communism in 1949. Despite the testimony by General Leslie Groves, head of the Manhattan Project, that it would take the Soviets twenty years to develop the atom bomb, August 1949 saw this event, and the beginning of war in Korea in June 1950 seemed to many as if it may have been a feint to draw Western forces away from a forthcoming thrust in Europe. Yes, Cold War sparring, Red spies, agitprop, suspicion--these helped prepare readers for The Body Snatchers, and of course for Robert A. Heinlein's 1951 The Puppet Masters, but Finney's novel does not have to be approached from this mindset. The book, after all, in its writing is as matter-of-fact as a Life magazine article, and the science-fictional notion of spores drifting slowly across interstellar space, from soon-to-be-ruined world to world to world, replacing one's most trusted friends and family with emotionless doppelgangers, is chilling. The Body Snatchers remains a top-notch, scaring read. 23 August 2014  I confess that when I think of Lester Del Rey, I happen to be rather more familiar with his 1950s YA works--The Mysterious Planet, Moon of Mutiny, or Rocket Jockey, for example—than I am with his adult pieces. I did read “Nerves” in Healy and McComas’ Adventures in Time and Space, and in the last couple of years I got around to The Eleventh Commandment and Preferred Risk, but it seems to be my teenaged readings of the juvies that have stuck with me. And while I of course had seen the 1971 Pstalemate on the shelves as a kid, I never picked it up...until recently, that is. Actually, I bought a copy at The Reading Place in Charlotte, MI, and then, maybe a year later, I apparently forgot I had it, so I picked up a different edition in the local library’s basement sale... Anyway, I finally pulled one off the shelf a few days ago and read the thing—definitely worth waiting for. Below is the review I did at Goodreads: https://www.goodreads.com/review/show/1031264524?book_show_action=false. Rafeeq Lester del Rey's 1971 Pstalemate is an intriguing and nuanced tale of a man who suddenly realizes--despite his disdain for what he regards as merely a "current fad in science fiction," despite his singular lack of luck at any sort of guessing games, and despite apparent common sense--that he himself possesses psionic power. It makes no sense to bight young mechanical engineer Harry Bronson. Or...well, does it? Occasionally, after all, Harry has flashes of inexplicable dread, or even voices seeming to call him. His complete failure at guessing Rhine cards, moreover, actually is just a little too complete, a statistical aberration no less than had he gotten them all correct. And certainly his own past is strangely shrouded, with all memories of life before age ten, and of the death of his parents, now lost to amnesia. But telepathy exists, the unwilling Harry discovers, and even precognition, too. His own parents had set up some kind of colony or commune of believers, now disbanded, of which little is known anymore, and he begins as well to be able to sense the mental presence of others like him in sprawling New York City. Yet he senses also something he can term only "the alien entity," a force utterly unknowable and frightening, and which seems to be trying to take possession of him. Extrasensory perception, a researcher's lifelong notes reveal, first truly manifested itself following a mutation caused by petrochemical pollution just three generations earlier. Yet although the people whom the increasingly sensitive Harry from a distance comes to recognize as fellow telepaths seem, in general, more decent than the average human being, he begins to realize that he finds only the young, never the old...for some intrinsic factor of the mutation drives all to inescapable madness. And now Harry's precognition tells him exactly how long he has: three months, and then descent into the living hell of insanity. Despite his delayed awareness of his abilities, Harry Bronson actually may be the strongest telepath still living. But he has only three months to solve the mystery of himself, lest he lose his own self, and this strange mutation prove merely an evolutionary dead end rather than a transformative quantum leap in consciousness. As Harry and his new wife, once his childhood friend and a telepath as well, race desperately for an answer, Lester Del Rey explores with subtlety and insight the very fundamentals of the human condition--growth and maturity, love and sexuality, and the nature of consciousness--and thereby gives an exciting, intriguing, sometimes touching story. 20 August 2014

Well, I just hit one of my favorite bookstores today, The Reading Place in Charlotte, Michigan, to pick up four new Heinlein books: the nice early '60s "techno" Starman Jones by Berkey at left, an uncredited Glory Road, a Menace from Earth by John Melo, and an uncredited Unpleasant Profession of Jonathan Hoag that captures the feel of the title story quite well. Now these have been scanned and added to my galleries of cover art. Of course, the real work was adjusting my library to accommodate the new purchases. My books all are alphabetized strictly by author and then title--except series (which are shelved according to plot chronology) and history (which are organized by geographical region, then alphabetized by title)--so any new additions require shuffling all the other books that are downstream. I think this took about half an hour, but it does make finding things later awfully easy indeed. In any event, these four covers now are in their appropriate galleries. And I confess that for my next used book run I may have my eye on an old Podkayne of Mars and a new Time Enough for Love... Rafeeq |

AuthorAuthor of several dozen pieces of literary criticism, reference entries, and reviews; novel Student Body; memoir Tiger Hunts, Thunder Bay, and Treasure Chests; how-to The Bibliophile's Personal Library; humorous Have You Ever Been to an Irishman's Shanty?; some poetry; and quite a bit of advising/Banner training materials. Archives

May 2024

Categories

All

|