It’s been quite a while since I’ve read, say, Eric Frank Russell’s Men, Martians, and Machines or A.E. Van Vogt’s The Voyage of the Space Beagle, but I found this maybe half a notch below what I remember those other two to be. I seem to recall the Russell being a bit less serious, mind you, but for the adventure it was, it was just fine.

Still, this early Clement was indeed decent fun, and worth reading. Below is the review I did at Goodreads:

https://www.goodreads.com/review/show/1036418510?book_show_action=false

Natives of Space is a 1965 repackaging of three 1940s Hal Clement novelettes from, it appears by the Street and Smith copyrights, Astound Science-Fiction.

Assumption Unjustified of 1946 follows a pair of aquatic aliens who stop off on Earth to withdraw some blood--painlessly and carefully--from an unconscious Terran for use in a rejuvenation treatment. Mildly amusing attitudinal irony abounds, but the aliens' mistaken conclusion at the end is a whopper, and therefrom springs the title.

The 1943 Technical Error is one of those classic puzzle stories of the humans-must-figure-out-ancient-alien-technology variety. Here the only hope of spacemen marooned on an asteroid by the meltdown of their atomic motors is to make use of a seemingly inscrutable alien ship before their air runs out. It is good as far as it goes, but modern readers might the piece frustrating because the artifact, with its recognizable ion engines, electrical cables, and whatnot, simply isn't alienenough.

Impediment of 1942 returns to the third-person-alien point of view when telepathic moth-like creatures from a low-gravity planet must try to communicate with a human in hopes of finding on Earth the materials with which to replenish their ammunition supply so that they can return to their feudalistic, warring solar system. Clement's investigations on the biochemical nature of thought are interesting, but the notion that the human character, "like many people, involuntarily visualize[s] the written forms of the words he utter[s]" is a gimmick that seems completely divorced from reality...

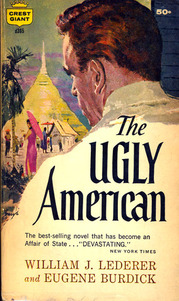

So long as the reader understands that, despite its funky mid-1960s cover, Hal Clement's Natives of Space actually is a product of the simpler days of the pulp magazines circa 1942 to 1946, it can be considered a decent three- to four-star read. Rounding up a tad, I'll call it four.

24 August 2014

RSS Feed

RSS Feed