Enjoy,

Rafeeq

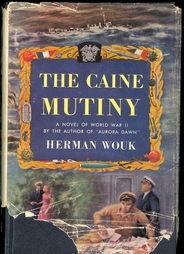

I've always enjoyed the film version of The Caine Mutiny and hence was excited at last to find an old 1951 printing of the novel itself. As I rather expected, Herman Wouk indeed had done a marvelous job, both more detailed and also subtler than the ensuing film.

To anyone who only has seen the movie, for example, the depiction here of Willie Keith's initial shallowness and then slow growth to maturity will come as a wry delight. Willie in the film, after all, is something of a Mama's boy, and certainly unused to real effort or discipline, but he also seems a young man proud to receive his naval commission and at last take the fight to the Japanese. The original novel, however, first introduces the Princeton graduate's naval career as merely a stratagem to avoid being drafted for presumably even more dangerous combat in the Army.

Prior to his belated, seemingly patriotic gesture, Willie was but a shallow playboy, someone feeling very grown-up to be receiving an actual salary for banging out pleasantly obscene ditties on nightclub pianos...a pittance more than supplemented by the allowance from his mommy, in whose house he still lives. He has "passed the first war year peacefully" as only a man with "one of the highest draft numbers in the land" can (9); after all, "A very high draft number, in those days, helped a man to keep calm about the war" (10). After Pearl Harbor he had made a brief show of considering joining up so that he can be talked out of it, whereupon Wouk archly gives us one of the best lines in the entire book: "So it was that Willie Keith sang and played for the customers of the Club Tahiti from December 1941 to April 1942 while the Japanese conquered the Philippines, and the Prince of Wales and the Repulse sank, and Singapore fell, and the cremation ovens of the Germans consumed men, women, and children at full blast, thousands every day" (10-11).

Clearly, then, it will be a long, long climb into manhood. Wouk handles it all very nicely: the indignation of the pampered college boy unused to criticism from this lessers, the confused understandings, the eventual maturity so slowly and subtly arrived at that no one, least of all Willie, could point to a single defining incident and say, "That was it." After long sea duty, though, when the now-skilled sailor looks over some newly arrived crewmen much like his earlier self, Willie doesn't like what he sees, and we therefore see how far he has come.

In depicting the painful growth of shallow young Willie Keith, who must learn much before he can find integrity and purpose and even love, Herman Wouk explores the conflicting emotions and the self-deception common to humanity, and he occasionally turns a beautiful phrase well worth a wry smile. Willie's first glimpse of the slovenly deck of the Caine, where "[o]aths, blasphemies, and one recurring four-letter word filled the air like fog" (66), is memorable in its own way, yet so, too, in another way, later, is the surprisingly touching evocation of the strange loss of purpose that accompanies the end of the war, along with the equally poignant scene of the final decommissioning of the aged and battered ship. The Caine Mutiny is a five-star read that captures powerfully the conflict within as men struggle in the conflict without that decided the course of our modern world.

24 May 2015

RSS Feed

RSS Feed