I cringed whenever the main characters ventured out of each other’s sight. I frowned at their attempted rationalizations of the unbelievable things they had seen. I gaped when, after finally having captured a cop’s service revolver, the protagonist ends up throwing it away because he cannot carry it inconspicuously—Come on, Doc, no jackets in 1955...? Really, though, every sidestep and piece of self-doubt made perfect sense, and it simply set us up all the better for the time when the baddies trot out the fuller explanations.

In any event, below is the review I posted at Goodreads:

https://www.goodreads.com/review/show/1034719193

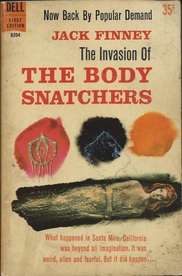

Jack Finney's 1955 The Body Snatchers is an exquisitely terrifying story of alien invasion which, despite the basics of its plot having become cultural tropes in the succeeding decades, remains as suspenseful as the day it was released.

Point of view, style, and setting here work together to make the unbelievable seem completely possible. First-person narrator Dr. Miles Bennell is the perfect character to deliver this story. The small-town doctor is well-educated, of course, and as a lifelong resident, he has the good general practicioner's eye for detail and tolerant understanding of human behavior, along with an intimate knowledge of the residents, geography, and history of the city of Santa Mira, California, population 3,890. His prose is matter-of-fact, sometimes wry, sometimes mildly self-deprecating, and when he begins by "warn[ing]" us that the tale "is full of loose ends and unanswered questions" and admitting that he "can't say [he] really know[s] what happened, or why, or just how it began, how it ended, or if it has ended," we are hooked.

The 1950s small-town setting then allows Finney both a nostalgic backward look and the firm grounding in prosaic reality needed by any good story of extraterrestrial invasion. The direct-dial telephone has been put in only within the previous year, for example, and the sexual tension between the divorced young physician and his divorced high school friend Becky Driscoll, with its mixture of amiable man-of-the-world roguishness and rather touching hesitance, is a subtly rendered portrait of early postwar mores. The familiar streets of the town, the back yards and porches where Miles played as a boy, the countryside where he hunted rabbits with a .22--in the warm sunlit day, all of these belie the seemingly impossible thing, human and yet not, that he and Becky see in the nighttime basement of the grim and frightened Jack and Theodora Belicec. Yet see it they did.

Finney here is a master of the night, and much of the action of the novel takes place after the comforting sun has set, in creepy basements lit by a single overhead bulb or by a dim penlight, on deserted roads where anything, anything at all, might wait in the dark beyond the headlights, in locked rooms where to sleep might mean to lose one's very self. Back and forth Finney deftly works us between the utterly shocking evidence seen firsthand at night and the sheepish uncertainty of plausible-seeming explanations in the morning. Clues are parceled out adroitly, and the protagonists' doubts, even as we wish to shake them into immediate understanding, are achingly believable. Yet eventually even these level-headed people must admit to themselves that something awful truly is going on, something inexplicable and threatening, a conspiracy that grows and grows, unseen and unsuspected by anyone but themselves.

The era of The Body Snatchers was, of course, ripe for such beautiful literary paranoia. Once the war had been won and the world apparently made safe for American ideals again, why, new threats suddenly lurked everywhere. The Berlin Blockade of 1948 brought American and Soviet armed forces to a precarious standoff in Occupied Europe, while the hugely populous former ally of China fell to Communism in 1949. Despite the testimony by General Leslie Groves, head of the Manhattan Project, that it would take the Soviets twenty years to develop the atom bomb, August 1949 saw this event, and the beginning of war in Korea in June 1950 seemed to many as if it may have been a feint to draw Western forces away from a forthcoming thrust in Europe.

Yes, Cold War sparring, Red spies, agitprop, suspicion--these helped prepare readers for The Body Snatchers, and of course for Robert A. Heinlein's 1951 The Puppet Masters, but Finney's novel does not have to be approached from this mindset. The book, after all, in its writing is as matter-of-fact as a Life magazine article, and the science-fictional notion of spores drifting slowly across interstellar space, from soon-to-be-ruined world to world to world, replacing one's most trusted friends and family with emotionless doppelgangers, is chilling. The Body Snatchers remains a top-notch, scaring read.

23 August 2014

RSS Feed

RSS Feed