Below is the review I did of the first volume on Goodreads:

https://www.goodreads.com/review/show/1186185286

Rafeeq

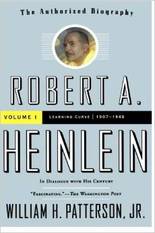

The first volume of William H. Patterson's Robert A. Heinlein: In Dialogue with His Century is a fascinating read for anyone interested in perhaps the most famous and influential name in modern science fiction. Based upon wide research in Heinlein's personal correspondence, and also upon seemingly countless interviews and e-mails with Ginny Heinlein and others, the text is engagingly written, and backed up with copious footnotes well worth examining. After giving a useful little history of the family into which Heinlein was to be born, Patterson takes us from the birth of the author-to-be in 1907 through 1947, his breakout from the "pulps" like Astounding Science-Fiction and into prestigious "slicks" such as The Saturday Evening Post.

The beginnings of Heinlein's career are interesting, of course, and yet so, too, are the details of the boy's relentless self-education, the youth's career in the Navy before being invalided out due to tuberculosis, and--though, at least for myself, to a lesser extent--his early Leftist political activity. Patterson reveals Heinlein's 1929 marriage to Eleanor Curry, a year-long union that was lost to history until the twenty-first century, but it is the story of his 1932-1947 marriage to Leslyn MacDonald that is particularly eye-opening. Heinlein's second marriage--which for decades was called his first--is something about which most fans knew only vaguely, as his marriage to Virginia Gerstenfeld from 1948 onward always loomed largest. Robert and Leslyn were, however, married for fifteen years, and it is quite touching to see, not just from Patterson's evaluation but also even from Robert's letters to Ginny after the breakup, how truly devoted they were for so long. It is interesting as well--though not surprising, perhaps, to anyone who has read Heinlein's fiction from the 1960s onward--to learn that Robert and Leslyn occasionally visited nudist resorts, and that his first two marriages were open, or "swinging," relationships. Most likely Heinlein was a fairly private person in any event, but such details help explain his drive to bury so thoroughly the history of his life with Leslyn. These were things that a children's author of the late 1940s and 1950s simply could not afford to have noised about.

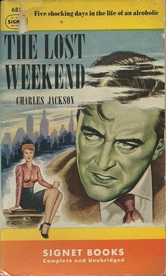

Patterson's book follows the Heinleins' work as civilian employees for the Naval Air Experimental Station during the Second World War, Robert's momentous move into the "slicks" and the beginning of what was to be a twelve-year association with Scribner's for a series of "juvenile" novels, and Leslyn's decline into alcoholism and the simultaneous growth of the relationship between Robert and Ginny. The ultimate failure of Heinlein's second marriage is surprisingly bittersweet after reading of the long years of such companionship and support, but of course we, the readers of half a century later, knew it was coming. The rise of Heinlein's final love, however, is perhaps even more reassuring, and thus a fine place for this first volume to end.

31 January 2015

RSS Feed

RSS Feed