Below is the review I did on Goodreads:

https://www.goodreads.com/review/show/1147722336

Rafeeq

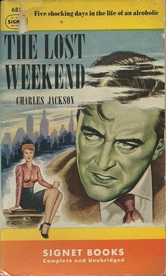

Charles Jackson's 1944 The Lost Weekend is a gripping probe into the mind of an alcoholic--the euphoria and the terror, the self-congratulation and the remorse, the understanding and the turning away. Really, as long as the term probe is used, one might reach next for lancet or scalpel, but of course such would not be fitting. These tools, after all, slice straight and clean, yet Jackson's artful third-person-limited prose and the artfully tipsy stagger of his plotting that hints, reveals, withholds, reveals in bits again is like a corkscrew, or perhaps some piece of fractal geometry that slithers into the corrugations of the brain, and somehow opens the gray matter up for inspection.

Many are familiar with the film adaptation starring Ray Milland, which of course is superb for its day, but of course Jackson's original novel is better. Avoiding spoilers, let us just say...well, that the book may not be quite as cheery as the film, perhaps. Many memorable images and scenes from the movie indeed do come straight out of the text: the bottle on the string--but, oh, how long we will wait for this in the book!--the planned trip to the country with brother Wick, the disappointing of bar "hostess" Gloria, the endless sweating stagger to pawnshops closed for Yom Kippur, the woozily confident purse caper in the restaurant, the fall down the stairs and the meeting of the creepy, faintly predatory male nurse Bim, the delirum tremens-induced vision of squeaking, bleeding mouse devoured by carnivorous bat.

Whereas Milland's character in his youth actually had been a promising writer, however, with a story published in the Atlantic Monthly, here Don Birnam is a nothing and a nobody. Oh, he had potential, certainly--everyone could see it. His second-grade teacher even wrote a gushing letter to Don's mother, saying that he was the brightest and most promising pupil she had ever had. At age ten the sensitive lad studied his face in the mirror as he cried at the realization that his father truly had abandoned the family and would never come back, and as a teenager he made it a point to write a poem every night, no matter how late he had to stay up. He knows his "Poe and Keats, Byron, Dawson, Chatterton--all the gifted miserable and reckless men who had burned themselves out in tragic brilliance early and with finality"--and this brand of genius of course has an allure to "[t]he romantic boy."

Don did not have even a year in college--that little incident with an upperclassman in his fraternity, wherein seemingly natural hero-worship led to a letter rather too warm not to lead to scandal and disgrace with fortune and men's eyes. Nevertheless, he is well traveled and beautifully well read. Switzerland, France, England, Greenwich Village--been there. Shakespeare, Byron, Chekov, Joyce, Fitzgerald--read 'em. But he can imagine being a writer, and writing the great novel of drunkenness and promise and self-deception and revelation, only when half-soused...just as he imagines being a master concert pianist despite not yet having learned to play, or being a great actor despite never having performed, or professing to a class on F. Scott Fitzgerald despite not even having earned a B.A. degree. Many a film makes such alcoholic pretension seem humorous, but just as the Milland version does not, neither has the source novel. The ironies are sad and grim, the situation frustratingly inescapable.

Jackson, then, is the great literary revealer that Don Birnam, regardless of his French and his German and his jaunty allusions to works up and down the canon, cannot be. How can a single drink just to start the fun lead to another of seemingly benign effect, then to a larger one, another taken in a gulp, and a few more no longer counted, as reason jumps by flea-hops from topic to topic, grows elliptical, finally sinks into the mire of a blackout? Jackson shows us, in a deeply introspective style that deftly pulls to the surface his central character's submerged motivations, his strengths, and his weaknesses with the same eye for detail that gives us an irresistible seven-page travelogue of the 65-block stagger lower, ever lower, through the socioeconomic strata of New York City. In the end it is Charles Jackson's gritty, forthright, and yet delicately rendered novel itself, not the actions of Don Birnam, that give any hope for the future.

30 December 2014

RSS Feed

RSS Feed