Rafeeq

The splashily packaged 1951 A Matter of Morals by Joseph Gies is an interesting little read--not great art, of course, yet definitely not the soft-core porno suggested by its beautifully leering cover art or its overblown, even misleading back blurb.

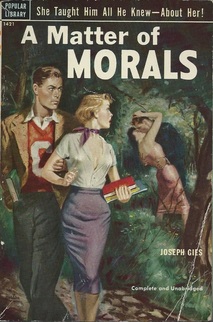

The cover of my 1953 Popular Library reprint depicts a professor-type fellow in the woods passionately kissing some bent-back gal while a letterman and his good-girl girlfriend hurry disapprovingly down the trail. Despite their obvious disapproval--it is a matter of morals, after all--the supposedly shocked coed looks open-mouthed over her shoulder rather more than is polite, and the artist has painted her blouse opened so deeply at the neck that no brassiere possibly could be worn. Ah, furtive Fifties semi-sleaze!

The novel itself really is only semi-sleazy, though. Yes, there's some drinkin' and some neckin' after the big game in automobiles on lonely roads and on the wide verandas of sorority houses; the secretary of the Chair of History has had a few affairs; and youngish Assistant Professor Vic Townsend does indeed entertain certain stray thoughts of flirtation and perhaps more when his wife and children are out of town for the week. Despite the promises of the first page of advertising blurb, however, there exists no "Delta Gamma 'Love Couch'" upon which "almost every man" supposedly enjoys the sorority queen, and conflicted, rather wishy-washy Dr. Townsend is no "Greek god," let alone "ready to take off the glasses at a moment's notice. If a coed was interested, that is..." (1).

The intertwined tales of nervous Townsend and his acidic wife, the vulnerable yet hot-to-trot secretary of his boss, the unctuously overbearing Dean Telfer, and the staff of the independent student newspaper are tolerable fiction of the middling three-star variety. For 1951 it probably is a tad racy, though sex is mainly offstage, except for brief, chapter-closing hints, as when at the end of a double-date, the half-drunk boy in the back seat with the sleeping date blinks into the front seat at the heavily breathing, shadowy form that turns out to be two figures, "one superimposed upon the other" (65), or when the professor who comes in out of the rain suddenly realizes that the secretary has no other clothing beneath her robe, and "[h]is trembling hand slip[s] inside" (108), or when the once-shy undergrad reporter finally gets to second base with the glossy blonde sorority girl: "It was the first time he had ever touched a woman's breast; it was indescribable" (132).

Easy as it is to be waggish about the titillation of yore, one should note that A Matter of Morals has some positives. One is the conflicted natures of Townsend, secretary Evelyn, editor Emmering, and reporter Slidell; each has a great deal of indecision and self-doubt beneath a seemingly composed and confident exterior, which is a nice touch, though Gies sometimes does spread it on a bit thick. The time of setting is intriguing, too--the novel begins in October 1938, just days after the Munich Conference--and yet despite some characters' discussion of appeasement, the Spanish Civil War, and whatnot, these tantalizing threads go nowhere. There are occasional potentially interesting whiffs as well of Red panic, casual anti-Semitism, classism, and easily hushed-up police brutality, but, frustratingly, these lead nowhere either. Finally, stylistically, point of view bops around from head to head rather much, which weakens the work for the reader of discernment.

For a period-piece quickie-read, A Matter of Morals is not that bad at all, though lasting literature it ain't, and the gap between the mild raciness of the actual text and the campus-Sodom-and-Gomorrah schtick of the completely misleading packaging sits rather strangely indeed...

17 May 2015

RSS Feed

RSS Feed